Registration Cancelled

All unsaved registration information entered during this session has been deleted.

Thank You

Transactions

Registration Checkout

The Continental Marines: Origin of Black Marines in America

The Marine Corps was first formed by the direction of the Continental Congress consisting of two battalions of Marines. Initially, the Congress anticipated that that the personnel for the Marine Corps would be furnished by General George Washington from his own Continental Army. However, General Washington had a shortage of men without any to spare for the newly formed Marine Corps. The Marines had to recruit their own personnel.

The first recorded Afro-America to enlist in the Continental Marines during the American Revolution a black man by the name of John Martin (called Keto) a slave of a certain William Marshall of Wilmington, Delaware without the knowledge of his owner. It is documented that on April 1776, he embarked aboard the Continental brig Reprisal in Philadelphia and later went down with his ship near Newfoundland in October, 1777.

The second black Continental Marine was Isaac Walker, who enlisted on August 27, 1776 in Captain Robert Mullins Philadelphia Company of Continental Marines, followed on October 1, 1776 by a third black Marine named simply “Orange”As of April 1, 1777, both remained on the muster rolls, and served at the second battle of Trenton January 2, 1777, and at the Battle of Princeton. These few black Marines were pioneers and were not succeeded by other until 1942.

Later, however, strong political forces compelled Washington to ban the recruitment and enlistment of men of color though they have fought gallantly in numerous military campaigns. Therefore, when the Marine Corps was formed in 1775, the ban continued for 167 years until June 25, 1941, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 which ended discrimination in the defense industry and the Marine Corps. But because segregation still existed they were forced to train at a separate facility at Camp Montford Point, New River, North Carolina. The very first black battalion of these Marines was the 51st Defense Battalion, honorably known as the “Mighty 51st”.

Black Marines on the U.S.S. BLADEN

Black Marines on the U.S.S. BLADEN

Combat on Iwo Jima

USS Bladen (APA-63) was a Gilliam-class attack transport that served with the US Navy during World War II. The USS Bladen was boarded by African-American Marines and departed the west coast for Pearl Harbor 20 November 1944 and upon arrival embarked personnel of the 103rd and 109th Construction Battalions for Guam. On 27 January the USS Bladen set sail for Iwo Jima, via Saipan. The attack transport debarked troops and provided logistic support during the assault and occupation of Iwo Jima (19–28 February, 1945).

Combat in Okinawa

After a brief layover at Saipan, Bladen prepared for the invasion of Okinawa. She performed her logistic services during the initial strikes against, and occupation of, Okinawa (1–10 April).

The largest number of black Marines to serve in combat took part in the seizure of Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands, the last Japanese bastion to fall before the atomic bomb and the threat of invasion of the home islands combined to bring the war to an end. Three ammunition companies, the 1st, 3d, and 12th, and four depot companies, the 5th, 18th, 37th, and 38th, of the 7th Field Depot arrived at Okinawa on D-Day, 1 April I945. Later in the month, the 20th Marine Depot Company came in from Saipan and in May the 9th and 10th Companies arrived from Guadalcanal and the 19th from Saipan.

The black Marines on the attack transport USS BLADEN (APA-63), the 1st and 3d Ammunition Companies, the 5th Depot Company, and part of the 38th Depot, and those on the USS BERRIEN (APA-62), the rest of the 38th and part of the 37th Depot, took part in the 2d Marine Division demonstration landing off the southeast coast of Okinawa. At the same time the assault troops of the Tenth Army (III Amphibious Corps and the Army’s XXIV Corps) went ashore on the western coast at the narrow waist of the 60-mile-long island. In the feint attack, the men climbed into landing craft, rendezvoused, formed assault waves, and roared in toward the beach, turning around 500 yards from the shoreline. The next day this maneuver was repeated in hope that it would prevent the Japanese commander from moving troops north to oppose the actual landings.

On 3 April, most of the black Marines landed on the island, ready to support the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, the assault troops of the III Corps. The Japanese had concentrated their defenses on the south, but there was more than enough action in the north to keep everyone in III Corps busy before the two Marine divisions moved south to join the main battle. Japanese air raids were frequent, mostly aimed at the cluster of ships offshore, and the barrier of antiaircraft fire thrown up loosed a deadly shower of shell fragments that often fell on the troops near the beaches. One Montford Point Marine by the name of Albert Hunter (Detroit, MI) recounts his experience aboard the USS Bladen which suddenly came under attack by Japanese airplanes. Immediately, he jumped upon the anti-aircraft gunner torrents and began firing upon the Japanese nearly scoring a direct hit on one of the Japanese planes. Many of the casualties suffered by the black units occurred in April, when their camps and work areas were still relatively near the front lines. The 5th Marine Depot Company had Three Marines of the 34th Depot Company on the beach at Iwo Jima, (l to r) PFCs Willie J. Kanady, Eugene F. Hill, and Joe Alexander.

The Civil War – Montford Point Connection

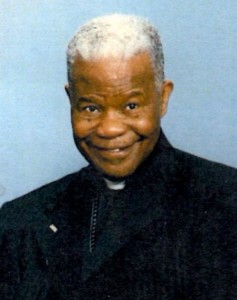

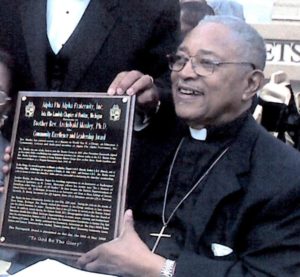

Robert Smalls (Civil War Hero) Dr. Herman Smalls Rhett-Final Roll Call

Former Past President of the Montford Point Association, Dr. Herman Smalls Rhett is author of the book entitled Final Roll Call which chronicles some of the stories of Montford Point Marines and includes platoon photos, and pictures of the Montford Point Marines matriculated through recruit training at the segregated Camp Montford Point at Camp Lejuene, N.C. during WWII. In the second and final edition of Final Roll Call, Robert Middleton, President of the Montford Point Marines in Detroit, Michigan collaborated with Dr. Rhett in contributing photos of more than a dozen WWII Montford Pointers who missed being included in the previous edition.

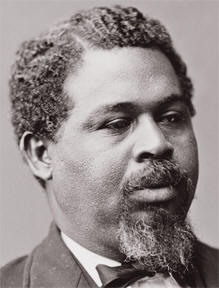

Dr. Herman Smalls Rhett (deceased in 2014) was a native of Charleston, South Carolina. According to the Executive Director of the Charleston S.C. Historic Society informed Dr. Rhett that he was a direct descendant of Civil War hero Robert Smalls, also from Charleston, S.C. Robert Smalls became a Naval hero of the Civil War for the Union in the American Civil War (1861-1865) He was forced into the Confederate Navy at the outbreak of the war, and made to serve as wheelman aboard the armed frigate “Planter.” On May 13, 1862, he and 12 other slaves seized control of the ship in Charleston harbor and succeeded in turning it over to a Union naval squadron blockading the city. This exploit brought Smalls great fame throughout the North. He continued to serve as a pilot on the “Planter” and became the ship’s captain in 1863.

After the war, Smalls rose rapidly in politics, despite his limited education. From 1868 to 1870 he served in the South Carolina House of Representatives and from 1871 to 1874 in the state senate. He was elected to the U.S. Congress (1875-79, 1881-87), where his outstanding political action was support of a bill that would have required equal accommodations for both races on interstate conveyances. After the Compromise of 1877, and as a part of white efforts to silence African American political power and rights, Smalls was wrongfully charged and convicted of taking a 5,000 bribe five years earlier in connection with the awarding of a printing contract. He was pardoned as part of a deal in which charges were also dropped against Democrats accused of election fraud. In 1895 he delivered a moving speech before the South Carolina constitutional convention in a gallant but futile attempt to prevent the virtual disenfranchisement of Blacks. A political moderate, Smalls spent his last years in Beaufort, where he served as port collector (1889-93, 1897-1913); he died on Feb. 22, 1915.

WWII PATCHES WORN BY MONTFORD POINT MARINES

WWII PATCHES WORN BY MONTFORD POINT MARINES BETWEEN 1942-1949

51st Defense Battalion

52nd Defense Battalion

13th Fleet Marines Forces

18th Depot Company

Fleet Marine Force Pacific

History

HISTORY: THE MONTFORD POINT STORY

The “ Mighty 51st” Defense Battalion

The first African-Amercan combat unit in the Marine Corps was the 51st Defense Battalion initially designated in June 7, 1943 whose principle armament became the 90mm antiaircraft weapon. On August 18, 1942, Col. Samuel A. Woods activated the nucleus of the 51st Defense Composite Battalion becoming the first Marine officer to command a unit of African-Americans. The outgrowth of various re-designations such as the 153mm Gun Battery which expanded to the 155mm Artillery Group with its machine gun group becoming the Special Weapons Group resulted in the inclusion of the 20mm and 40mm cannon and .50 caliber machine guns. Titles of these units changed and the word “Composite” was dropped from the name to accommodate the Marine Corps table of organization for defense battalions whereas the 155mm Group became the Sea Coast Artillery Group and the 90mm Antiaircraft Artillery Group.

The 51st Defense Battalion Surpassed USMC Gunnery Records on the 90mm Anti-Aircraft Weapon

Members of the 51st Defense Battalion underwent intensive training on weapons and a myriad of equipment including fire control equipment, and searchlights. While training, the Montford Point Marines surpassed all standing Marine Corps gunnery records under the leadership of GSgt Henry, a native of Detroit, Michgan. During firing exercises, in the presence of the Secretary of the Navy Knox, and General Thomas Holcomb, they had the distinct experience of first hand observation of the Montford Point Marines as they fired the 90mm Anti-Aircraft weapon at a sleeve target towed through overhead airspace, and hit the moving target within 60 seconds. Not only could they make direct hits on the target, but also on the dollies that pulled the sleeves targets. This performance was never matched by other anti-aircraft weapon units at that time. One of the first black Marines to make rapid advancement through the ranks of the Marines Corps, was a Marine named Henry Baul who resides in Detroit, Michigan, was promoted to the rank of Gunnery Sergeant and commanded operations in the 90mm anti-aircraft gun pit, belovingly known as “Top Gun”.

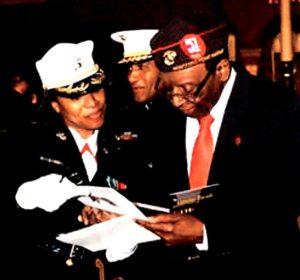

In May,1991, Mr. Henry Baul along with other co-founders Joseph Burrell, and Edsel Stallings, co-founded the Montford Point Marine organization in Detroit, Michigan. In May 16, 2008, the second highest ranking African-American Lieutenant General in the Marines Corps, Lt Gen. Ronald S. Coleman personally invited GySgt. Baul (accompanied by Robert Middleton) to Washington D.C. to be honored with distinction, at the Evening Parade at Marine Corps Barracks, 8th & I St.

Founder GySgt. Henry L. Baul

Baul receives Honors from Lt.Gen Ronald S. Coleman

On February 1944, the 51st embarked aboard a merchant transport ship; USS Meteor, at San Diego sailed for the Ellice Islands to provide a garrison for Nanomea Island. Later the 51st Defense Battalion; moving by landing ship and submarine chaser, disembarked at the island of Funafuti under the command of Colonel LeGette to set up outpost at Nukefetau.

WWII Patches

MONTFORD POINT MARINES ON IWO JIMA (WWII- February 1945)

The intent of the United States for invading Iwo Jima was to establish an airstrip for the purpose of attacking the mainland of Japan. Enitiwok was the staging ground for the military assault on Iwo Jima. Almost 900 African-American troops took part in the battle of Iwo Jima, including Sgt. McPhatter. On February 19 1945 Thomas McPhatter found himself on a landing craft heading toward the beach on Iwo Jima. McPhatter said, “There were bodies bobbing up all around, all these dead men,” said the former US marine, now 83 and living in San Diego. “Then we were crawling on our bellies and moving up the beach. I jumped in a foxhole and there was a young white marine holding his family pictures. He had been hit by shrapnel, he was bleeding from the ears, nose and mouth. It frightened me. The only thing I could do was lie there and repeat the Lord’s prayer, over and over.

Marine Sgt. Gene Doughty had the first squad of the 36th Depot as they landed on Iwo Jima. He recalls that they were four (4) all black Marine companies that landed on Iwo Jima, however, two (2) black companies that landed on D-Day; The 8th Ammo Company and the 36th Depot Company. Doughty’s squad of the 36th Depot received orders to guard the airstrip at Motoyama airstrip. On D plus five, Doughty saw the raising of the flag on Mt. Suribachi.

Marine Archibald Mosley was also part of the 36th Marine Depot Company were amongst the first to see combat and bullets on Iwo Jima. He says it was very difficult to dig a foxhole because after a small distance downward, the sand would just cave in and fill the hole you were trying to dig. This made troops highly susceptible to enemy fire. Being a part of a Depot company meant that Marines were carrying equipment, ammunition, and fuel which was the most dangerous thing in the world. One night Marine Mosley and his unit came under a Bonsai attack by the Japanese, killing a black marine (named Babyface) while he slept in his foxhole. Marine Mosley was awaked by his foxhole buddy (Wilbur) as he engaged hand-to-hand with the enemy. Marine Mosley, said while in basic training, members of his platoon had jeered him, because every night he said his prayers. Often he crawled into the sack sniffling because everybody was laughing and calling him a “momma’s boy”. However, on the night of the Bonsai attack, when “Babyface” was critically wounded, those very same individuals were begging him to pray for the fatally wounded Marine that everybody loved.

Marine S.L. Roberson, also saw action on Iwo Jima where black marines and soldiers of the U.S. Army in charge of transporting marines from ship (PA-33) to shore were killed outright by Japanese artillery and gunfire while performing their duties. Bodies floated in murky blood tinged ocean water on the beachhead, where lifeless bodies and body parts floated on the surface. Members of the Ammunition and Depot companies would take direct hits, blowing the bodies of marines and the equipment they had in tow up very high up in the air.

Montford Point Marines and the Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima

Marine Sgt. Thomas McPhatter, (later a Vietnam, Lieutenant Commander in the US Navy), even had a part in the raising of the flag. “The man who put the first flag up on Iwo Jima got a piece of pipe from me to put the flag up on,” he says. Of course this is absent from history. Often Blacks and Native Americans were excluded from operational war photos for the purpose of promoting and selling U.S. Savings Bonds. “One of the marines said that the people who were filming newsreel footage on Iwo Jima deliberately turned their cameras away when black folks came by.

Melton McLaurin, author of the book entitled; The Marines of Montford Point, says that there were hundreds of black soldiers and marines on Iwo Jima from the first day of the 35-day battle. Although most of the black marine units were assigned ammunition and supply roles, the chaos of the landing soon undermined the battle plan. “When they first hit the beach the resistance was so fierce that they weren’t shifting ammunition, they were firing their rifles,” said Dr McLaurin.

Roland Durden, another black marine, landed on the beach on the third day. “When we hit the shore we were loaded with ammunition and the Japanese hit us with mortar.” Private Durden was soon assigned to burial detail, “burying the dead day in, day out. It seemed like endless days. They treated us like workmen rather than marines.”